Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California, August 13, 1979

From Uncommon Places: The Complete Works © 2004 Stephen Shore

Sheldon: All of your work seems to be sharp, there's no shallow depth of field.

Shore: There are a couple of pictures, but not many. There's one in Uncommon Places of a silver mailbox in Florida and the background is out of focus, still readable but slightly out of focus, and then a few years earlier there's the green car in upstate NY and again the background is this funky town out of focus. As far as I recall in the book those are the only two. That goes back to the beginning and what you were saying about a picture being read, and having a picture with a great depth of field and lots of points of interest. My tendency is, if I see something interesting, to not take a picture of it, but to take a picture of something else and have that in it so that you can move your attention around, like this is a little world that you can examine, and for those kinds of pictures it simply makes more sense for everything to be sharp.

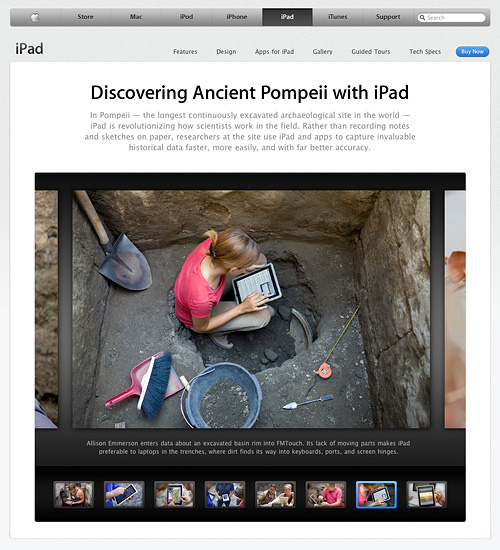

White: Noah and I were talking earlier about the iPhoto books, with respect to the idea of the way an image or an artifact ages. You talked about American Surfaces that way in an interview I read. You said that you were aware of how the photo would look after a certain period of time, given the changes in the landscape. The first time I saw the iPhoto books I thought about that, about how contemporary they are in design, and the decision on your part to embrace that. Then I thought of looking at them in 20 years. How do you think they'll be different?

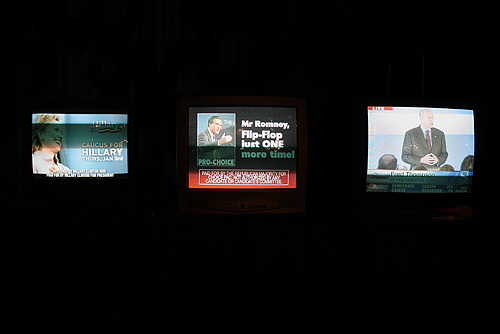

Shore: With some of them I'm actually thinking explicitly about that. One series of books I started a couple of months ago. I think of them as time capsules, and I do them on days when the New York Times has deemed it worthy to have an eight-column headline. You can go a year and not have one, or you can have two in a couple of months. So last week it was when Scooter Libby was indicted, and the last time was when the levy broke in New Orleans. And so on those days I start with a picture of the front page of the New York Times, with the headline, and then I go around and take pictures of what's going on that day. Suddenly I'm thinking about style, and what clothes look like, or cars, or the prices of things. But I'm also interested in what ordinary life is on that day.

In the "60s I was spending a lot of time in Europe, and I was in Europe in '68, when a lot of shit was going down, as they say in the States, including the Kent State shootings. I remember reading the Herald Tribune every day, and it just seemed that the country was falling apart. But a year or so later I was in Europe again, and it didn't seem like there was anything as dramatic going on, but again I had the feeling of things falling apart. And I realized that it was because all I was getting was the news. And the news wasn't reporting that bees were pollinating flowers in Dutchess County today, and the sun rose at 6:51 just as predicted, and that the law of gravity held today as one would hope. If all you're getting are these points of news, you're missing the fact that the world's not falling apart. It's the real stuff, the stable stuff, that doesn't get reported. And so the books, my time capsules, have some of that in them too. So there are things that are very specific to a period in time, what movies are playing, but also just what ordinary things look like.

Sheldon: People are looking at your work from the seventies now more than they were then. I was recently looking through some un-published stuff from Las Vegas, in '73 or "74, and it's incredible. Las Vegas was tiny! To me it was incredible to look at this place that I know well. I think photography generally gets better with time, do you think about that?

Shore: I was to some extent aware of that. I remember thinking that it's important to put cars in photographs because they are like time seeds. And I learned this from looking at Evans. I can go to New York and find a building that was built a hundred years ago. I can take a black and white picture of that building and it would be hard to know when it was taken. But you put a modern car in front of it and it dates it. That's what I saw in Evans's work, though Evans would sometimes put an old car in the picture. I'm interested in that dating, like styles of renovation in buildings. I was thinking about that then. But I guess you're asking why is there a resurgence of interest in my work?(laughter) I think there are certain questions that are more right for you as a critic to answer than for me to answer. But I'll give you mine, which is not meant to be exhaustive, but maybe somewhat cynical and humorous. I like to think there is something intrinsically strong about the pictures and that's why they survive, but on top of that I'll tell you that the interest began in the 90's when people saw a connection between my work and the Becher students. They started working backward and looking at my work again, which had not been looked at for a few years. But I think there's something else that is more related to what you've been asking about, and it's this. I was interested, particularly in the series American Surfaces, in taking pictures that felt natural, so they didn't look artified. It looked like looking at something. I was interested in what the world looked like.

There's a phrase in Shakespeare that meant a lot to me. Hamlet is telling the meaning of acting and ends by saying it's "to show the very age and body of the time its form and pressure." And that was a phrase that was in my mind when I was doing some of this work. And the work was shown a lot, so I'm not saying it wasn't popular or well received in the "70's. There was a lot of negative stuff being written about, but it was being shown. But something else happens when time passes. If I'm being successful at showing what the modern age is, people may not have enough distance from it to appreciate it.

Sheldon: Exactly!

Shore: You know? It's like, this is just what life is! Why photograph it, if this is just what life is? And then maybe 30 years later they can talk about "Oh it looks like the "70's," but I'm sure this is what today looks like.

White: I thought it was really wonderful at the show a few years ago at the 303 Gallery, to see the work from the "70's and along with the books from the past few years. It brought up the big artistic problem of the invisibility of the present, of the style of the present. Which is, I don't notice how my jeans look right now because they just look ... normal … but in ten years, you notice. (laughter)

Shore: And that was sort of the trick of the work. Trying to look at the present world with a bit of distance so that there's an amazement at…you know…this is how our jeans look.

White: I'd be interested to hear you talk about your commercial work from the past few years, and just how different it is to work in that situation, with a client and an art director and all that. Is it that different?

Shore: The one big campaign I did was that different. The art director was in London. He's sitting in an office in London with a drawing of an airport, what he wants the picture to look like, and it's not based on anything but his imagination. And then we get location scouts and find some place where that can be made and go ahead and make it. And it's a kind of visual problem solving that's fascinating, but very different than my going out with a camera to take pictures. It's fascinating: here's what we want it to look like and then we go out and do it, but the whole thing is fun and you have a producer and the assistants are incredible and it's just a lot of fun to do. And I'm being hired for my ability to visually organize space. We had to find an airport that would fit with the art director's drawing and we had scouts in about six or seven cities in the United States and a couple of places in Europe to find an airport where we could do this one particular shot. I actually picked an airport, but they didn't like it, but I said I knew that I could make it look like the picture. We actually went to the airport and they thought this isn't quite right, and I said this is going to be right because I could understand how the camera was going to see it. They could see it with their eyes, but they couldn't understand how it was going be transformed into a picture.

White: Has the commercial work impacted your other work?

Shore: I haven't seen an impact. One thing that was interesting doing the commercial stuff is that you go in knowing what can be done in post-production, and you just take that into account.

Sheldon: With the iPhoto books, do you think of those images strictly in a book form?

Shore: After the fact I've thought that I could do something else with some of them. With a lot of them I'm using tiny little cameras that you can't make a big enough print to do anything with. But really the answer to the question is while I'm shooting I'm only thinking about it as a book. They're all done in one day and so it's all meant to be one work that I'm thinking about during the day. I'm thinking about how they're going to relate to each other in a book. It's not like at the end of the day I collect my pictures and make a book, the idea for the book is happening as the pictures are being made.

Sheldon: In a lot of your work there's this layer of humor, which is very important. There's one iPhoto book that kind of looks like the Italian Riviera,

Shore: The French Riviera.

Sheldon: There are these two great pictures where Ginger's lying down sunning, with basically identical framing. Ginger's face on the bottom and then there's a beach scene. In one picture there's a young, very beautiful woman in a bathing suit walking by, and then you turn the page and there's an older guy in the same exact place, and the picture is the same. (laughter) Brilliant! There's a lot of slapstick.

White: It seems like the book format lends itself to game playing on some level.

Shore: That's exactly right. And I feel like it's open to playing with all those opportunities. And so I'm not even thinking about how the different books look with each other, really. I can see someone coming in and thinking that it's the work of six different people. It could be a class assignment, and that kind of interests me. I could have an idea that I want to pursue for a day, but I'm not interested in beating it to death and doing the same thing over and over again for a year.

White: So over your career we have your mental evolution, your development as someone who takes pictures. But I was also thinking about our collective evolution, as people who look at pictures. It must be different for us now to look at photographs from the "70s because our culture of looking has changed.

Shore: Well, I'll pick two specific things particularly related to American Surfaces. I got a good bit of recognition in the 70's for Uncommon Places. Not for American Surfaces. No one liked American Surfaces, except for two people: the gallery director who put it on and Weston Naef, who is now the head of photography at the Getty. But at that time he was at the Met, and he bought the entire show, which is now in the collection of the Met. Years later I ran into Nan Goldin, who told me that she liked the show a lot. But no one else has ever said a kind thing about it! (laughter)

I think first of all it was about color. People just weren't accepting color then. Again, I'm not talking about general ways that human perception has changed over 30 years. I'm talking about something very specific, the attitude towards color has completely changed. The other thing was that American Surfaces was presented as a grid. I don't think people could look at grids then. My sense was that it was viewed as a kind of wallpaper, as a bunch of color around a room, and it was very hard for people to focus on the pictures, and think about the relationship of the pictures, and penetrate it

The reason I'm thinking this is that there were a few people who worked at the gallery, the show was up for about three months, who after a month or so said, "You know, it kind of grows on you." This is something that was one my mind doing the current hanging, which I wanted to make reminiscent of the original hanging. The original prints were un-matted and un-framed and closer together and I think by framing them and matting them individually it separates them, and makes it so you have the sense of the grid but also makes it easier for people to look at individual pictures. But I think also something else has simply changed: people are now used to seeing pictures presented in a grid. And simply the reaction to color is completely different, it's just not an issue, but then it was absolutely an issue.

Sheldon: How did you imagine selling that work? Did you perceive selling it as one body of work?

Shore: Yes.

Sheldon: Besides the person at the Met did any one else bite?

Shore: No.

Sheldon: I saw some black and white pictures you did in the late "90's, the large inkjet prints of forests and trees. This was the first time I know of that you worked in black and white after your early work from the Factory. It was at a time when art photography was mostly in color, and I think some people couldn't access the work because the black and white put them off.

Shore: I'm interested in conventions. Why are there certain conventions? What happens if you don't follow a certain convention? Sometimes my reactions are not a radical departure, but a reactionary departure. So if everyone is doing color I think there's nothing wrong with black and white, you know?

Sheldon: Could you talk about what you were interested in with the baseball photographs?

Shore: It could not be simpler. I love baseball. When Ginger and I were dating and first living together in "77 and "78 we were probably averaging 30 games a year, and in those years we went to every home game that Ron Guidry pitched. He was at the peak of his form and it was amazing to watch him. This was a large part of my life and some of those people were my absolute heroes. The third baseman for the Yankees, Graig Nettles, was one the most eloquent baseball players I've ever seen play. It's the simplest thing. I like posing problems for myself. The idea of photographing a sport with an 8x10 camera, it's interesting.

Sheldon: The idea of finding those exposures, 1/8th of a second, 1/15th of a second.

Shore: Some are faster, but part of it is that in a number of different motions there are often moments of rest, so if a batter is waiting for a pitch and is going like this (gestures) the moment that the ball leaves the pitcher's hand he goes (make a gesture) but only for a fraction of a second before he starts to swing. But if my timing is right I get him like that, there's all this kinetic energy but he's absolutely still. There's this one point of balance or transition of energy that, if your timing is right, you can stop the action with a view camera.

I don't know if you've ever seen any of the black and white New York street pictures I've done. The idea of doing Winnogradesque street photography with an 8x10 camera, I thought, this would be interesting to do.

Sheldon: What year were you doing those?

Shore: 2000 to 2002. You may not have seen them, because the only place they were published was in Tate magazine. I was using a Deerdorf 8x10. Deerdorf made a wooden slide that popped into the back that covered up half the frame so you could do a 4x10 inch negative and then you can slide it and on the same sheet of film do another 4x10. These are long thin pictures that I'm making 40x100 inch inkjet prints from. My thought was that you could take a Leica around New York with you and wait to pounce on something, or you could set up a 4"x10" on 57th street and stand there and in a couple of minutes something is going to happen! (laughter) What I found is that I've never been more invisible on a New York City street. The only time anyone ever said anything is when a woman told her young son, "that's what old cameras used to look like." (laughter)

The only time someone really had a conversation with me about it was when a policeman came up to me on 57th street between 5th and 6th. He told me he used a 4x5, so we started talking and at one point he asks my name, and I tell him, and he says, "I have your book. I show it to my family and they think your pictures are boring, but I tell them they don't understand." (laughter) So where I'm photographing the people walking by, there's a car that's double parked at a slight angle. While we're talking the guy is about to get in the car and the policeman says, "Do you want me to stop him?" He's not even thinking about ticketing the guy! He just knows the car fulfills a structural need in the frame! (laughter)

© 2005 Noah Sheldon & Roger White

back to home...