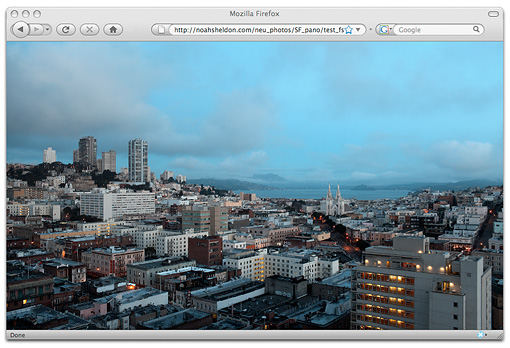

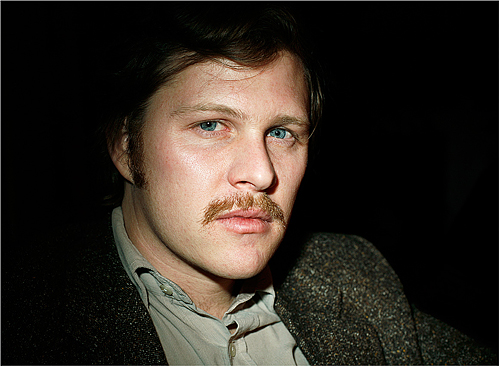

Brian Eno photographed by Noah Sheldon

I had the privilege of photographing one of my heros - Brian Eno.

For your reading pleasure, a great unpublished interview with Brian Eno by Lester Bangs from 1979.

Brian Eno: A Sandbox In Alphaville

By Lester Bangs

1.

The other day I was lying on my bed listening to Brian Eno’s Music for Airports. The album consists of a few simple piano or choral figures put on tape loops which then run with variable delays for about ten minutes each, and is the first release on Eno’s own Ambient label. Like a lot of Eno’s “ambient” stuff, the music has a crystalline, sunlight-through-windowpane quality that makes it somewhat mesmerising even as you only half-listen to it. I had been there for a while, half-listening and half-daydreaming, when something odd happened: I starting thinking about something that didn’t exist. I was quite clearly recalling a conversation I’d had with Charles Mingus, the room we were in at the time and the things he’d said to me, except that I had in reality never been there and the conversation had never taken place. I realized immediately that I was dreaming, though I had no memory of falling asleep and had in fact passed over into the dream state as if it were an unrippled extension of conscious reality. So I just lay there for a while, watching myself talk to Mingus while one-handed keyboard bobbins pinged placidly in the background. Suddenly I was jolted out of all of it by the ringing phone. I stumbled in disorientatedly to answer it, and hearing my voice the called asked: “Lester, did I wake you?”

“I’m not sure,” I said, and told her what I’d been listening to. She just laughed; she was an Eno fan too.

Brian Eno, one of the emergent giants of contemporary music, can be a truly confounding figure. Everything about him is a contradiction. He’s a Serious Composer who doesn’t know how to read music. What may be worse, he’s a Serious Composer who’s also a rock star. But what kind of rock star is it that doesn’t have a band and never tours, also enjoying the feat of being allowed by his various record companies (mostly Island) to put out an average of two albums a year since 1973 when none of them has sold more than 50,000 copies? (In the midst of this prolific output, he was quoted in pop papers everywhere, insisting that he was not a musician at all.) A man who (artistically speaking) goes to bed with machines and lets chance processes shape his creation, yet dismisses most other modern experimental composers for the lack of humanity in their work. Everybody’s favorite synthesizer player, who says he hates that instrument.

Listing all the projects he’s been involved with in his career so far is a bit like trying to enumerate the variegate colors and patterns on a lizard’s back. With Bryan Ferry, he was a founding member of Roxy Music, one of the watershed rock bands of the Seventies. He’s been part of the Scratch Orchestra and the Portsmouth Sinfonia, two famous experiments in mixing musicians from the entire spectrum of technical facility, from virtuosi to people who couldn’t play at all, in the same performing situation. He has engaged in several ambient collaborations with Robert Fripp, co-piloted the last three David Bowie albums, and guested on sessions all over the map, from Matching Mole to a remake of Peter and the Wolf. He has produced Television, Ultravox, Devo and Talking Heads, and his standing with New Wave rockers in general is summed up by the graffiti which recently appeared in several spots around the New York subway system: “Eno is God.” And yet, for all his support of musical primitism (he produced Antilles’ controversial No New York anthology of Lower Manhattan saw-off-the-limb bands), with his interest in the sociology of mechanical systems he’s an avowed cybernetician, which he calls his “secret career.”

The first time I interviewed him I had no real plans for doing a story; I had been following his work for years, and just wanted to find out what kind of guy he was. I didn’t expect much, really, or rather what I expected was either some narcissistic twit or more likely a character whose head was permanently lodged in the scientific/cybernetic/conceptual art clouds. Somebody who might be nice enough but was just a little too… ethereal.

The person I did meet that day was relaxed, gracious, and, to use his favorite word, one of the most interesting conversationalists I’d run into in some time. Unlike most rock people, he was interesting in lots of things beyond music and kicks; unlike many academic types, he recognized that a lot of the things he was interested in were somewhat arcane or overly theoretical, and that the jargon some of these concerns inevitably arrived in was incredibly dry. “Most of what I do has been thought about rather than talked about,” he said at one point, “and my resources of information are kind of quasi-scientific, which means that the language that comes out is really objectionable in a way.” He seemed kind of amused by this, when not at pains to make sure he wasn’t boring his guests to death. One of his biggest problems seemed to be people who wanted to impress him and acted like they knew what he was talking about when they really didn’t, letting him go on and on and on when he knew he had the tendency to get carried away. The clincher came at the end of the interview; it was getting towards dinnertime, and suddenly I had this picture of a Britisher who for all I knew didn’t have that many friends here, sitting in his hotel room in Gramercy Park all night, so I asked him if he’d like to get something to eat and then come over and listen to some records. “Sure,” he said, and then “Uh, say… um… would you happen to know any nice girls you could introduce me to?”

Which was certainly something Ian Anderson never said when you interview him.

Not long after that he moved to New York and I’d see him around town now and then, at clubs and concerts and such, and he was always friendly, open, curious about others and just plain nice in a way that few rock star types are. I met Robert Fripp, Carla Bley, Phillip Glass and several other Serious Music sorts around the same time; they were similarly easygoing and down-to-earth, and eventually I concluded that (as opposed to those rock stars always trying to flatten you with their hideous old personas) this must be what real artists were like.

About a year later, one summer Saturday afternoon, I was sitting in Washington Square Park with a friend. I had been trying to get in touch with Eno through his press office without much luck, because he would be lecturing and appearing on panels during the weeklong New Music, New York avant-garde noise and conceptual tiddlywinks festival just beginning in Lower Manhattan’s Kitchen Center for Music, Video and Dance, and I figured that would be a good place to catch him in action. My friend and I were sitting there discussing the comparative merits of various current purveyors of sonic aggravation, when suddenly I looked up and said, “Hey, isn’t that Brian Eno walking this way?”

Sure enough it was: blonde hair already balding at thirty, alert blue eyes, sensual mouth, and functionally simple but expensive clothes. He came and sat down, cheery as ever with that bemused expression whose innocence can make him seem at various moments the seraphic artiste or cherubically childlike. Every time a pretty girl walked by, his head would swivel and he would comment admiringly, like either a kid at a parade or a guy who’d just got out of prison. I mentioned that I was getting ready to do a story on prostitution, interviewing call girls from a midtown agency that advertised in Screw, and he said: “I called for a girl in response to one of those ads once. It said ‘Unusual black girls.’ So I phoned and said, ‘Just what do you mean by unusual?’ They said, ‘Just what did you have in mind?’ I said, ‘Well, I’d like one that was bald with an astigmatism.’ ‘Well, we’ll see what we can do,’ they said. They found the astigmatism but no the baldness.”

“Why astigmatism?” I wondered.

“I’m terribly attracted to women with ocular damage.”

I wasn’t sure what to say to that, so I changed the subject to music: had he heard the new Joni Mitchell album of songs co-written with Charlie Mingus? “No, I bought it but immediately gave it away. I’d like to record with Joni Mitchell. I like her in that one period: Blue, For the Roses, Court and Spark. Since then, I don’t know–Weather Report strike me as all people who are continually promising with no delivery.”

We arranged to meet the next day, when he was appearing at the New Music festival panel with Philip Glass, Jerry Casale, Leroy Jenkins, Robert Fripp and New York Times columnist John Rockwell. Subject: “Commerciality, Mystique, Ego and Fame in New Music.” It was mildly dreary and mildly titillating, as these things tend to be; things were livened up mainly by Fripp doing a rather theatrical vibe-out on the photographers in the room, and a woman from some relatively arcane socialist sect who asked the last question, a seemingly interminable muddle about the relationship of all this New Music to spiritualism. The reaction of the room ranged from cynical laughter to mild irritation, but Eno quite patiently and politely tried to respond to whatever points she was trying to bring up, by talking about some of his own recent studies in shamanism and certain points of interesting intersection he’d noticed between the roles of the shaman and the rock star. (The next day, of course, the festival’s daily newsletter said what everybody else had been saying: “Eno thinks rock stars are shamans.” “Shit,” he said, “I knew they were gonna take it that way.”)

That afternoon as we walked back, I mentioned it myself, and said, “When I hear the word ‘shaman’ I reach for my revolver.”

“I don’t think it’s a word we should be so afraid of,” he replied. “Being afraid of it only imputes to it more of those qualities we disliked in the first place. Lots of people are shamans. As for the conference, it should have begun where it ended. I don’t tend to sit and think things through when alone, and I often find that it’s when I’m confronted by others with the contradictions and inaccuracies in my own way of going about things that I’m able to think them through and make some sort of change. I do like being put on the spot. Everyone else it seemed wanted to go on and on talking about the economics of the music business, but when that woman, whom everyone else seemed to hate, got up and started asking me about the spirituality involved in all this, I thought ‘Ah, now at last we’re getting somewhere.’ Perhaps precisely because it is such a difficult and delicate topic.”

“But,” I said, “don’t you think one of the things wrong with a lot of experimental music is this emphasis on ersatz ‘spirituality?’”

“No. I think the trouble with almost all experimental composers is that they’re all head, dead from the neck down. They don’t trust their hearts, I think, and tend to take themselves with a solemnity so extreme as to be downright preposterous. I don’t see the point, really. I’ve always abandoned pieces which succeeded theoretically but not sensually.”

We walk on a bit, and he comments admiringly on another passing girl. “I’ve developed a technique recently that works rather well, I think.” I expect him to start talking about musical techniques, but then he says: “I lean on a parking meter, and every time a beautiful girl walks by, I smile at her. If she smiles back, I invite her up to my flat for a cup of tea. I moved to New York City because there are so many beautiful girls here, more than anywhere else in the world.”

A bit later we’re talking about the effect of travel on creativity, and he says, “I’ve got four apartments. One in London, one in Germany, one in Bangkok and one here. Whenever I’m not in one of them, I let one of my friends stay there. I went to Thailand because I said to myself ‘I must get away for six months, away from everything.’”

“What do you do there?” I asked, barely able to fantasize what such a place might be like.

“Met Thai girls. I’m fascinated by them, not just sexually but because they seem to possess an essence of femininity that is awesome. I don’t mean in the usual Western sense of passivity or anything like that–more something spiritual.”

I ask him, “Are you romantic? Do you fall in love a lot?”

“Well,” he says, “I guess I must be romantic because I really enjoy kissing. In fact, I think it is much more intimate than fucking. Then again, there is one girl with whom I have a very close romantic relationship which isn’t really particularly sexual at all.”

The next day we meet again to attend one of the evening concerts at the Kitchen. This is my first avant-music festival, I have very little idea what to expect, and ask him if he plans to attend the full nine days of nightly shows of five or six separate composer-performers each. “I’m here today doing research, really. Looking for people who might fit into certain parts of my own projects.” And then he warns me: “It’s good at these kind of things to sit as close to the door as possible, both because of the stuffiness of the room and if the music gets too bad you can sort of duck out for a moment and have a cigarette.”

He’s right about the room. There’s only one fan in an extremely large loft-type space, and as I sit being lulled by its whirrings (Eno having procured two chairs from the management and placed them almost in the door) I realize that in this context, context is everything, that I could be listening to “Fan Piece” by somebody or another. I know that’s corny, but then so is a lot of the avant-garde, and I’ve found fans a mesmerizing rockabye probably since I was dandled on Momma’s papoose knee, back in church.

Which, in terms of audience rapt for dronings, was what the Kitchen was like. The first performer recited a piece containing many, many repetitions of the words “Dutiful, dutiful ducks,” and showed slides of a person with a sheet over his or her head wandering through empty football bleachers. The second act (each of them allotted twenty minutes so, as Eno explained, “if one is too excruciating you at least know they won’t be up there much longer”) was a young woman in leotards who took off her high heeled pumps and used them to prop up the speakers emitting her music, which she tilted and left at a rather precarious angle; I can’t remember what the music sounded like. Next was a one-man band singing about how clear the air was in the Colorado Rockies, followed by two guitarists jamming to a tape of random noise. (Eno’d been eyeing the girlfriend of one all evening; about her swain, he said, “He looks like the kind of guy who if you asked him what kind of women he liked, would say ‘I’m into gazelles, man,’” and he was right.) We missed most f their set, and got back in time for a young woman who played a tape of herself singing and sang against that: long, slow, oppressively droning pieces with lyrics to the effect that she had been abused all her life by the school system and the New York State Unemployment Bureau but nevertheless she was just a human being who couldn’t keep her own house clean. “Boy, you oughta see my apartment,” I thought, as Eno got up and went out for a smoke; I stayed behind because she was so dolorously depressing I kind of liked her. He returned in time for someone named David Van Tieghem with something called “A Man and His Toys,” which involved the composer winding up all sorts of rackety little thingamabobs and letting them clitterclatter around each other, also unrolling a sheet of that plastic packing paper with all the bubbles in it and walking across it popping bubbles with his toes at odd intervals. I could only stand half of that before I had to take a walk myself, and that was the last act of the evening.

A few minutes later, Eno came walking out. “I quite liked him,” he laughed. “By himself it isn’t much, but I think all he really needs is a context. I’d like to take him and let him do that stuff in the middle of a whole bunch of other kinds of percussive things. For my next album I’m planning one piece where the performers would be in separate rooms where they either couldn’t hear each other, or only slightly. I think you could get something interesting out of that.” A few weeks later he would play me a tape of his latest recording session, and there, in that very separate-performer take, in the middle of all sorts of other strange instrumental juxtapositions, was van Tieghem with his toys. And of course Eno had been right: in this context those odd whirrs and rattles added a whole other dimension.

We went to a Thai restaurant where he ordered some food which he was then too embarrassed to eat when he saw that the rest of us had only ordered beer. So he called over our protestations for four small plates and divided up the portions evenly between all of us. While we were eating, a young woman present mentioned the previous day’s conference and asked him: “Do you think you have charisma? Do you work on developing your mystique?”

“Let me think a moment so that I can formulate an intelligent answer,” he said. “People tend to cluster around me, so in that sense I think it could be said that I have charisma. As for mystique…well, when I was in school… I never thought about any of these things till I was fourteen. I thought I was terribly ugly and that I would never be able to get any girls. So I began cultivating certain eccentricities, or encouraging ones which might have been already present, figuring that perhaps then girls would like me. And I think to an extent that it worked. There was this one girl in school, Alice Norman, that I and everyone else was madly in love with, but she was so beautiful that she seemed untouchable. No one would ever dare approach her, certainly not me, because I was even more shy then than I am now. One day she just walked up and started talking to me; I couldn’t believe this was actually happening, but… I guess it worked,” he laughed.

“Sounds like the way you write music,” I said.

“Yes,” he laughed again, “yes, I guess it does.”

After that he invited us up for a while, having stopped off en route for cherries and ice cream. His flat itself looks exactly like what you would expect: airily minimalist. But though he travels and lives light (like many musicians, he had about twenty albums in his entire collection, and very few of them were rock), somehow finally it’s not the cybernetic oracle or professional roué that you remember but the kind and in some way simple man of such exceptional hospitality, who got excited as a kid when told “Baby’s On Fire” was a dancefloor favorite at a local club, who on another occasion went out of his way to buy medicine and take it to a woman who managed to alienate absolutely everyone on the local music scene just before contracting a serious illness. It would, of course, never occur to him to do otherwise. We talked on for a while that night, until I began to notice him drooping a bit. I walked over to one of the other guests, and said, “You know something, I think this guy wants to go to bed, and is too polite to kick us out.”

“I think you’re right,” she said, and we left. This was not the last time this would happen.

In the very first interview I ever had with Eno, he had just finished a lengthy cybernetic exegesis, when I said: “Okay, now let’s do what you do in your music: let’s make a complete 90 degree turn. Instead of talking about all this theoretical stuff, why don’t you tell me a little bit about your life, like say… what were your parents like?”

His face lit up. “My father was a postman all his life. He had exactly the same job from the age of fourteen until he retired a couple of years ago. Where I come from is Suffolk, which is in the east of England, a kind of underpopulated country area which really is, I suppose, still kind of a feudal society. There are sort of squires and local gentry, who aren’t resented and who in turn don’t control in a kind of unpleasant way. There’s just an assumption of a hierarchy, actually. And this is reflected by the fact that everybody votes Conservative there; it’s got about the worst record of Labour voting ever. It’s a very conservative society. A friend of mine said that people that are happy vote Conservative, and in a sense, he’s right.”

“Or people that are threatened,” I said.

“Yes, that too. At the lower level it’s people that are happy, and don’t see the need for changes. And in a funny way, I think my father was very happy. My mother is Flemish; she was in a concentration camp during the war, in labor camps mostly, actually building planes. She met my father at the end of the war and came to England, and in 1948 they gave birth to me.

“The interesting singularity about this area of Suffolk that I come from is that it’s a small town, like 5,000 people, but directly next to town, literally within five miles, are two large American air bases, huge ones, with a total population of about 15,000 GIs. So from very early on, nearly all of the music I heard was American music. Which to me was like outer space music. I can never explain to people what effect of that was, not Elvis Presley but the weirder things, things like “Get A Job” by the Silhouettes and “What’s Your Name,” Don and Juan, the a capella stuff that I had no other experience of–it was like music from nowhere and I liked it a lot.

“But I’ll say a bit more about my parents. The thing I find incredible about my father is that he never, ever cheats on anything. He’s incredibly honest in this sort of really ideal country way, that part of being a community is not fucking people about. You just don’t do it. He wouldn’t dream of cheating on his taxes or anything like that, or even slightly slotting them in his favor. There’s a real strong organic morality there that hasn’t been imposed, somehow, and that isn’t resented, either. It’s not the result of a set of laws. I know that the same thing exists in country areas of America, as well.

“But what’s interesting is that in the last fifteen years since I left that part of the world and moved to cities, when I revisit I find that that is actually degenerating now. There is a sense that, partly because the community just isn’t as insular anymore, it’s just not as integrated a community. People have moved and other people are more mobile, so you don’t have this rather carefully evolved locking together of personalities. The thing that’s always interested me about country areas is how eccentrics are tolerated, and not only tolerated but really have some actual part of social life. There was a guy we used to call Old Bill, who was a very very weird old man, sort of mumbling and grumpy and a really really ugly face. He used to just walk about, and his one ambition was to collect money for the brass band. When they were playing he used to go around and do it with his hat, and gave them the money. And so what he did was give him a uniform, and he was the happiest man after that. He had this thing to do, and of course the band was quite happy, and everyone was pleased. And in a city, he would either have become a tramp, or been put in a home or something like that. Nobody’s interested in that kind of weird social role anymore, in big places.

“My parents were both Catholic, and all of my education until the age of sixteen was Catholic. I went to a convent first, with nuns teaching, and then from the age of eleven I went to Catholic grammar school, and that had some interesting effects. I was the only Catholic in the area that I lived, and there was a kind of thing about that, being called a Roman candle in jest. There was never any kind of hostility about it; just felt a bit different, that’s all.”

“Do you think Catholicism had any effect on the sense of dread in a lot of your music?” I asked, thinking of pieces like “Driving Me Backwards.”

“I think so. Well, I trace the melancholy more to that, because one of the things, in fact the only thing I can remember from school was how I felt about these hymns: I thought they were absolutely beautiful, and the more sad they were the better I liked them. We were singing all the time, they do a lot of hymn singing in Catholic school. And though there was this you’ll go to hell thing, and nuns giving descriptions of what would happen to you there, I don’t think I took it seriously enough for it to leave a real impression, because when I was about fourteen the whole body of theory started to conflict with the way I wanted to behave, and I just chose the latter, without much guilt.

“I can also remember at about the age of nine, for some reason I became the class clown. I can’t remember anything I actually did; I can just remember keeping in balance this mixture of being bright enough to get by–so the teachers couldn’t actually get on my back too much–and also being kind of precocious at the same time, always managing to stay one up. I could actually do the work as well, because I was one of the brighter kids–in fact, I even used to quite consciously do a lot of sort of secret research, so that I could stay bright enough to maintain my freedom in that respect. My father bought this thing called Pear’s Encyclopedia, which was issued once a year by a soap company in England, and I used to just sit and read it–it wasn’t like an imposition, I liked reading it–and sort of cram it in until I had this huge head full of facts about things. I can remember a time also when this became very useful. There was a teacher called Miss Watson who was a very nice old lady. She said, ‘What does anyone know about the calendar?’ and it so happened that about a week before I’d been reading about the transition from the Roman to the Gregorian calendar, and I knew everything about it, like how long exactly in minutes and seconds the year was. And so I delivered this impromptu spiel which staggered them. I didn’t tell her that I’d just read it all up, and from that time on she sort of held me in awe, which gave me all sorts of freedoms in her class.”

“Do you ever see your current position as being somewhat analogous?”

“Yes, I hadn’t thought about that incident in a long while, and I was just thinking as I described it about whether that was also the case. What I do think is that my tendency to work by avoidance has strong roots in my childhood. One very strong thing that I can remember was a real decision that I took when I was nine, which was probably my first really important decision. I can remember my father coming home from work as he always did– he always had to work lots of overtime in order to get enough money, because the job wasn’t well-paid. I can remember him coming home from work and just falling into a chair and going to sleep because he was so tired he couldn’t even eat, and I thought, ‘The one thing I’m never going to do is get a job.’ I saw that it was a trap, because he was so tired and so exhausted on every level that he was never going to be able to do anything else but get up the next day and go to work. It turned into a distinct avoidance thing for me, because I never wanted to be in that position. That thought never left me: in fact, I’ve never had a job in my whole life, except once. When I say a job I mean something you do for somebody else to earn money, not because you want to do it. And I did have one job like that once. I did design and layout on a newspaper. It was an advertising magazine that was distributed free to a million homes. I didn’t hate it. I became very successful at it. I started off at the bottom, doing a very menial job, and in the four months I was there I got promoted again and again and again, and I ended up earning four or five times as much as I’d started with, and sort of running the office. And then I realized that I could carry on doing that and never do anything else, because I wasn’t doing anything else. And I kept saying to myself, ‘Oh well, I’ll do some music this weekend,’ and then I wouldn’t, I’d be too tired and I’d say, ‘Oh, I’ll do it next weekend,’ and then I wouldn’t do it, so I just gave it up after a while. It was exactly what I knew a job would be like–not horrible enough to make you want to get out, just well-paying enough to make you comfortable and to keep putting things off.

“So when I was about thirteen or fourteen I decided to go to art school, and it wasn’t hard to get in, because the art school I applied to was short of students and had to have a minimum amount in order to meet their funding. I didn’t have any real notions of being an artist at the time; I was interested in and very moved by painting, but the main thing was that I didn’t want a job. You don’t really have art schools here like we do in England. In England, which has a fifth of your population, there are about eighty art schools. Some of them are quite small, but again some of them are much bigger than anything you have here. They’re all the result of the William Morris movement, the idea that the masses could be cultured and so on. They always had this reputation of being the liberal education in England, and it’s always been the place where people who didn’t really know what they wanted to do except that they wanted to do something vaguely creative, would go. And art school staff have always been afraid of that idea–they knew that everyone didn’t come there with the idea that they would all turn out painters, but it was just like a scene where everyone kept going. Which is now threatened incidentally by Margaret Thatcher, who is cutting back the grants to such nonproductive facilities.

“The first art school I went to was a very, very unique and interesting one. It was run by a man called Roy Ascott, who had previously started another art school in London which Pete Townshend studied at, and quite a number of other interesting people. He’d gathered together the staff, and they’d quite effectively tried to work out a new policy of art education, with the idea that art had an important cultural role and wasn’t just to do with people making pictures. It was a center for creative behavior really; that’s what they tried to think of it as. Of course, they were always in this bind that the education committee demanded to see lots of paintings, and the fact that students were doing interesting music and theatre and dance and so on didn’t really interest them. They only wanted what was expected. So Ascott got sacked from the place that Townshend was at, and then he found a little old art school that was just sort of going to pot, and he started the same thing again there with the same staff. It only lasted two years, again he was sacked, he just keeps getting sacked all the time. He’s a brilliant guy. He was…well, I suppose you could say he’s a behaviorist, which usually has bad connotations to it, but in an art school context that’s just dynamite news. He was hated by the liberal arts teachers of England like nobody else. They used to publish all sorts of articles against him because the kinds of things he did, to anyone who wasn’t involved in them, must have looked very fascist. But they weren’t. They were really exciting.

“I’ll tell you the projects we had the first semester. You must realize that this is a real naïve bunch of students, all fifteen or sixteen, that come in with paint boxes thinking that they were gonna do Renoirs or something like that. I was involved by pure accident: it was the nearest art school. In fact, if I could have done, I would have gone to another one that I couldn’t get a grant for. This was just a crummy little place in a little country town, and this bunch of students all from the country, and all with ideas about the nice paintings they’d be doing. On our second day there, our first drawing exercise was to make a visual comparison between a venetian blind and a hot water tap. It was meant to be in terms of how they functioned, not in terms of how they looked. And this boggled everyone. And then the first main project was that the students were put in pairs, and each pair of students had to invent a game, the function of which was to make some kind of psychological behavioral evaluation of people who played it. So they weren’t necessarily competitive games, they were games that involved making a decision rather than a number of others, and then extrapolating things about people’s personalities on the basis of those decisions. I think there were thirty students altogether, so there were fifteen games made. They varied through all sorts of things: mine was a kind of board game, others were whole rooms that you went through and did various things in. Anyway, all the students went through this, and consequently each student ended up with fifteen so-called character profiles. From those character profiles you had to make what was called a Mind Map, which was a kind of diagrammatic scheme of how you tended to behave in lots of different situations, and then the next part of the project was that you had to then assume a character who was as far as possible opposite to that one, and that was who you were to be for the rest of the semester, which was like eight more weeks. This was very, very interesting. And then we were put into groups of five on the basis of these new assumed characters. The meekest person would be like the group policymaker, and the one who tended to talk most would be who got to do all the dirty work, like buying things from the shops. He would be the dogsbody; that was my job, actually. And so you had people working with characters who were quite alien to them. And each group of five had another project that was a very complicated one that I can’t explain, but we had to make the projects using those characters.

“There were some funny things (that) happened. There was one girl who was very timid, so part of her Mind Map stipulated that she had to walk this tightrope in front of the whole group every morning. This was her own stipulation, you know, these things weren’t imposed; having designed your own Mind Map you then worked out a number of behavior patterns that you carried out. Another interesting thing was that the whole accent of the course was on working with other people; you could act alone if you wanted, but the accent was on group dynamics and how people worked together. In fact, we went into that in quite considerable depth, about how you got things done in groups and what sort of behavior tended to be counterproductive and so on. It was all very useful. I’m happiest working with other people anyway. It was really like early training in Oblique Strategizing, collaborating, all the techniques I use now, and it was certainly the most important thing that could have happened to me at the time. That lasted only two years and then everyone got sacked again, and I went to another art school: one of the staff whom I got on with particularly well got a job in another school and said would I come along and be a student there. The first was Ipswich, the second was Winchester. And while at the two I studied under some wonderful people. Tom Phillips is I suppose the most famous now, isn’t he, quite a well-known painter. He wasn’t then; he was a very tough teacher, and we got on extremely well. That is, until I became a rock musician, and then he thought I was throwing my talents away. That was a very painful experience, for me and probably for him too actually. I also studied under Christian Wolff, an American composer who wrote a series of pieces for nonmusicians which were very important to me at the time, generally using untrained voice, or non-instruments like sticks and stones and so on; in fact, one of them was called ‘Sticks and Stones.’

“See, when I was at Winchester I got myself elected head of the student union, so that I could hire interesting staff. So I started getting people to come down and give lectures. We used to have a lot of composers coming down, like Cornelius Cardew and Christian Wolff and Morton Feldman.

“I didn’t know that I wanted to do music until I’d been at art school for about three years, although I’d been fooling with electronics and tape recorders since I was about fifteen. I had wanted a tape recorder since I was tiny. I thought it was just like a magic thing, and I always used to ask my parents if I could have one but I never got one, until just before I went to art school I got access to one and started playing with it, and then when I went to art school they had them there. I thought it was magic to be able to catch something identically on tape and then be able to play around with it, run it backwards–I thought that was great for years,” he laughs.

“I can remember the first musical piece I did at art school: the sound source was this big metal lampshade, like they have in institutions, and it was a very deep bell, and I did a piece where I just used that sound but at different speeds so it sounded like a lot of different bells. They were very close in pitch and they just beat together. It’s not unlike many of the things I do now, I suppose.

“Later at Winchester I build George Brecht’s ‘Drip Event.’ That was one of the best things I did in my art school days. George Brecht produced this thing called ‘Watermelon’ or ‘Yam Box’ or something like that. It was a big box of cards of all different sizes and shapes, and each card had instructions for a piece on it. It was in the time of events and fluxes and happenings and all that. All of the cards had cryptic things on them, like one said, ‘Egg event–at least one egg.’ Another said, ‘Two chairs. One umbrella. One chair.’ There were all like that, but the drip event one said, ‘Erect containers such that water from other containers drips into them.’ That was the score, you see. I did two versions of that. I did a simple one which won an award, but then I decided I wanted to do a big one. I made a ten-foot cube out of what you call speedframe here I think, we call it Dexene in England; it’s this metal that screws together. You can make big structures out of it very easily. On top of that I had a collector that collected water, then the water would be disseminated through a whole series of channels and hit little things and make noises as it went down. At the bottom of this cube there was a wall a couple of feet high all the way around, and the wall was covered with those things you get for the children’s painting books where you just put water on them. So over the few days it survived–it was wrecked by vandals– the water would drip, and it would splash onto these little pictures which gradually came to life very slowly. But it was a very lovely thing, it made the most beautiful delicate noise. I had the water just dripping onto little cans with skins stretched across them so that they made little percussive noises, little dings and tinkles and so on, a very very delicate noise, and it was right by a river, so the gentle bubbling of the river was in the background. But that got wrecked, unfortunately. It was outside and I never event got a photograph of it.

“I also did La Monte Young’s “X for Henry Flynt,” which was a good performance too. It’s a place that I can’t remember the exact score, but it stipulates that you play a complex chord cluster and that you try to play it identically and with an even space between it. There were two ways of doing it, since the score is ambiguous: you either play each one identical to the first, where you’re trying to always play exactly the same thing, or you try to play each one identical to the one before. I did two performances of that one: I did one like this”–he spreads his arms–”at a piano where it was just as many notes as I could cover, and I did another one with an open piano frame where I just used a big flat piece of wood, CRASH CRASH CRASH. It sounds horrible I know, but if you last ten minutes it gets very interesting. My first performance of it lasted an hour and the second one an hour and a half. It’s one of those hallucinatory pieces where your brain starts to habituate so that you cease to hear all the common notes, you just hear the differences from crash to crash, and these become so beautiful. They’re just entrancing. The difference can be like trying to cover both the black and white keys at the same time, sometimes you don’t get a white down properly or miss a black, and just missing one note out of the fifty or so you’re covering is a very noticeable difference, you really can hear that. You start to hear these omissions as melodies, or sometimes your arms creeps up a little bit further or down a little bit further or you hit too hard or your rhythm switches, and of course since I had the sustain pedal down as well it was just a continuous ring and eventually the whole piano was just really resonating and the richness of the sound was just amazing. After a little while you start to hear every type of sound, it’s the closest thing in music to a drug experience I’ve heard. You hear trumpets and bells and people talking clear words, sentences coming out, because the brain starts to–it’s like the opposite of sensory deprivation, but it’s the same effect. You start to hallucinate, because you telescope in on finer and finer details, like for instance the acoustics of the room become very very obvious to you. You notice that one note always echoes off that wall and another always echoes off that wall. And you can hear interplays like that in space as well, which of course are facts that in a normal performance you wouldn’t be aware of, since things are going by so quickly and they don’t repeat.

“But fortunately that thrill is something that doesn’t keep happening. Once you throw about the brain’s facility to habituate like that, it’s not something that you can keep using forever, I’ve found, because part of the thrill from something like that is that from such an economical source so much happens. Once you know that, there isn’t that thrill anymore; you sit down to another of those pieces of unchanging music and think, ‘Oh well, I know what’s gonna happen now.’

“Not long after that I joined a Cornelius Cardew thing called the Scratch Orchestra. I was only a member of that for a very short time. It was a group which ended up being about eighty people, mostly from art schools but also some composers and so on, and it was like a kind of music events type study group which also performed those things. It’s really hard to explain what went on in the Scratch Orchestra. There was a thing called the Scratch Book which was a dossier of all the pieces produced by people in the orchestra, and they ranged from conventionally scored pieces to very offbeat types of graphic material intended to produce music. It had a lot of offshoots: for instance, the Portsmouth Sinfonia was really an offshoot work since most of the people in it in the beginning came out of the Scratch Orchestra. There was another one called the Majorca Orchestra, then People’s Orchestra Music and lots of little groups who were very important in England for a while and absolutely nowhere else. The Portsmouth Sinfonia was already established when I joined it. I joined and just produced the two albums–well, in the loosest sense of that word. There was not much producing to do, since the first one was recorded on stereo, so mixing meant putting one channel up or the other.

“I joined the Sinfonia just after I left art school in 1969, and it was a great training. Anyone could join, provided they came to rehearsals, and the idea was that you play the popular classics as well as you could. Now everyone thinks that the Sinfonia was composed only of nonmusicians but it was wasn’t actually; it had this open membership so that anyone could join, so some very good musicians joined. That was what really made it interesting: this tension between people playing it really well and others making an absolute fuckup of it, but everyone doing it with full seriousness. The concert we did at the Royal Albert Hall was great. There was a girl who had actually trained as a concert pianist for many years, and her career had been ended because she walked through a glass door by accident and damaged her left hand. She knew she could still play very well, but she would never be a concert pianist now. Anyway, she joined the Sinfonia, and we did “Pathetique.” I think with her, it was some Tchaikovsky piece, she was playing these beautiful piano things, and it was one of those where you get the piano and then the orchestra coming in: “Pliddleliddleluddlelidliiidleliddle–BRAANH UHN AHN ER ONNKH!” I played clarinet. Not very well.

“It was around this time that I got into Roxy Music. In fact, I was in the two simultaneously. In fact, my last concert with Roxy was at the York Festival: I played in the Sinfonia in the afternoon and Roxy in the evening, like one after another. Actually that was also my last Sinfonia concert as well, come to think of it.

“I joined Roxy Music after it started as well. Well, just after. Bryan came from Newcastle Art School: he’d been in a soul band there with a guy named Graham Simpson who was the first bass player in Roxy, and they decided to come to London and start a band together. So it was just the two of them at first, then they advertised for a synthesizer player, and Andy MacKay went along with his little synthesizer. Then they found out that he also played wind instruments, and Andy said, ‘Oh, I know a guy who plays synthesizer, I’ll play saxophones and that, and I’ll get this other guy who knows electronics.’

“The truth was that I’d never touched a synthesizer before, but Andy knew that I had been doing things with electronics for a long time, five or six years, particularly using tape. Since I was about fifteen, really. They didn’t even ask me to play at the audition, in fact I was never auditioned. I got there on rather a false pretense actually, which is a good way to do it. I had tape recorders, and Andy said, ‘We want you to come along and just help us make some demo tapes of the band,’ and that’s all I thought I was going there for. Then I noticed there was a synthesizer around so I started playing around with it, and they said, ‘Would you like to join the band?’ So I guess in a sense it was an audition, but I didn’t know it was.

“I borrowed the synthesizer off Andy, and shortly after that he went away. He got a teaching job in Italy for a month or so, and I had this studio and these tape recorders, and I just started doing experiments with the synthesizer. It’s not a hard instrument, actually. People think synthesizers are difficult and mysterious, but in about a day you can understand how to use it. In about five years you can understand how not to as well.”

“So I joined Roxy about a month after it started happening, in fact I joined about four days after Andy. The band at that time was bass guitar, synthesizer, saxes and piano, a very peculiar lineup.

“We rehearsed for a long long time adding drummers and guitarists occasionally along the way. To get a drummer we auditioned 130 drummers, and it came down to tow people in the end. One was a guy named Charlie Hayward who played in Quiet Sun, which was Phil Manzanera’s first band. He was a very technical sort of drummer with a lot of interesting ideas; he had a drumkit that was made apart from ordinary drums, it had all sorts of junk inside it, like a van Tieghem type of thing only on stands so he could play it. So it was a choice between him who was very light and Paul Thompson who’s very very heavy, and we went for Paul, because we decided that with the instruments we already had quite enough etheria, we needed some kind of heavy anchorage. And I think that was quite the right choice as well. I think if it hadn’t been for Paul, who is always quite the overlooked person in Roxy, it would have been just another arty band.

“We spent a year rehearsing, first of all in Bryan’s girlfriend’s house and then in my house. I built a tiny little studio that was soundproofed off, and we worked in there really hard for about five months. We used to rehearse five nights a week. It was our only life–we gave up all sorts of social life. We never made any money because we never played live. I supported myself by doing two things mainly. I was wheeling and dealing, which meant that I used to buy electronic equipment, and knew where to buy things cheap. I was living in South London, which was a crooked part of London, and I just used to buy stuff up that was cheap, and sell it again. For instance, this chain called Pearl and Dean closed down their operations, they used to have PAs in cinemas and bingo halls, and I bought up all their loudspeakers and got a bulk discount. I bought 75 of these columns of loudspeakers and sold them all bit by bit, and some of them became part of the Roxy PA and that. So I used to do that and the other thing was, I made a few blue films. I didn’t feel bad about it; mostly felt tired. And it takes a long time, as well; not a long time in terms of Apocalypse Now, but it takes about two hours. And because you always do it indoors of course, you have to do it under these very bright lights.

“I was very happy in Roxy for quite a long time. I don’t think any of us expected to be successful, for a start. Well, Bryan did, I suppose. But for the rest of us it was still kind of (an) art event type of thing. I don’t think anyone would have been surprised or even especially disappointed if after a year it all folded up. In fact, it even looked like it might, at one point. We did our first live performance over a year after we’d got together, and then we did about a dozen performances in a dozen places with awful equipment and under very bad circumstances.

“Then we got signed. We had two supporters. First of all John Peel got us to do his radio program, and that was the first time I’d been in a recording studio. We did this session, and we did it very well, because it was our ideal situation: we’d been used to working in something like a studio in my place for a year. So we weren’t at all flustered by that situation, and we also had an idea or I did anyhow about how you could use the studio. We recorded five songs in four hours, and actually did a bit of overdubbing and so on. And the tapes sounded really great. They got broadcast, and the reaction was remarkable. Nobody had ever heard of us, we were completely unknown, Peel had seen us at a Genesis concert. It was a terrible concert. At this time I still wasn’t onstage yet. I used to be at the back of the hall mixing and synthesizing and sometimes also singing as well, which was a very weird role to be in: the audience is sitting there watching and suddenly this voice comes out and they look all around.

“At one point in this concert I remember Andy, who had a predilection for wearing large boots, stepped backwards onto the main DI box which fed about six instruments to the mixer. And of course everything went off because he crushed the fuckin’ box. We didn’t have any roadies, so the only thing for me to do was to set up a mix that I thought would be all right for the rest of the show and go and sit on the stage holding these bloody wires in! I didn’t have a soldering iron or anything, I couldn’t fix it. So I just sat the whole rest of the concert, holding the wires in like this. I felt like such a prat.

“So anyway Peel liked that. And then after that Richard Williams wrote about us in this column he used to have in Melody Maker called ‘On the Horizon,’ which was about unrecorded bands. It was our first press and very flattering as well. Then we used the Peel radio tape as a demo tape, took it around to a lot of places, most of whom were uninterested. Then we got in touch with E.G. Management, because we’d all been very impressed with how King Crimson were handled, and E.G. set up an audition where they hired this horrible big empty cinema in Stratton, and there were just these two people in the audience who sat there watching us and looking like managers. At one stage our new roadie, in an effort to look efficient, went running across the stage tripping over another of those main wires and ripping it out, so once again, there I was…perhaps that’s what people liked about me. Anyway, they rejected us, and then this Richard Williams piece came out, and they decided to give another listen and accepted us. We were a real mess in some ways at that time. It was all like good ideas but real untogether.”

That last sentence, in fact, would be a perfect description of Roxy Music’s debut album. Eno himself feels that Stranded, recorded a year later and their first LP without him, is really their masterpiece. It may well be, but in that album Roxy stopped being a vessel strong enough to hold both sonic experimentalism and Bryan Ferry’s fin du chicle romanticism, and settled instead for being perhaps the most opulently aristocratic pop group of the Seventies. Eno’s sonic miasmas were on one level no more than a frame of gilt smog, designed to better showcase tunesmith-vocalist Ferry, but on another they were the defining factor in the band’s air of mystery and avant-garde reputation, and as crucial as Ferry’s Basil Rathbone singing in establishing the group’s basic sound. The second album, For Your Pleasure, featured a ten-minute cut called “The Bogus Man” which represented all that was good and bad about Roxy with Eno: it was a failed experiment, but it at least pointed the way for others. This atmosphere of risk made the first album a bit cluttered yet diffuse–too many people trying to do too many things all at the same time–but the first side of For Your Pleasure is the pinnacle of the Ferry-Eno marriage, great songs in a setting that can only be called luxurious.

Meanwhile, Eno was stealing the show from Ferry, not musically but with his image–his flutterlashed amphetamine spider look on the inside of For Your Pleasure is alone worth the price of the album. Later he would abandon things like makeup and outrageous clothes both in and out of the public eye, opting instead for a more modestly functional look (even if he doesn’t always keep his shirts buttoned much above the navel), and looking back on those wild visuals today he says: “It was just a piece of work, a very interesting person that I made for a little while. It was a person that was slightly separate from me as well, and the problem with it was that it was very quickly became a limiting for a little while. It was a person that was slightly separate from me as well, and the problem with it was that it very quickly became a limiting identity because for one thing it scared everybody away,” he laughs. “Things like that act like filters, and this was acting as the wrong kind of filter. It filtered out exactly the kind of people that I wanted to meet, and attracted exactly the kind that I didn’t want to. You’d have to have some idea of the English trendy scene at the time… it just attracted assholes I didn’t want to have anything to do with. There was kind of assumed heroism about it, when in fact it was very easy to do. There’s nothing heroic about it in that kind of situation, because if you’re in a band you’re in a totally protected environment. It’d be a lot more difficult for a schoolteacher, say, someone who actually had to deal with people outside the same set of assumptions. It’s an easy way of getting a reaction, and being easy doesn’t cancel it out–I suppose what also happened was that I fell out of love with that aesthetic of… not shock, but flamboyance.”

Meanwhile, there were ego conflicts within the band–or, more precisely, involving the band vs. Bryan Ferry. “I’m sure Bryan felt threatened by me, and with good reason in a way. Roxy was his band he was certainly the driving force in it–without him it would have been like a bunch of fiddlers. He was the most important member beyond a doubt. Now what happened was that because of my image the press constantly focused on me. I’m not blaming the press for this. I was photogenic and I talked a lot in interviews where Bryan was quite taciturn, so all the interviews for a time were with me. I must say I was quite honorable in that I didn’t come on like it was my band, I always kept saying ‘It’s Bryan’s songs’ and all this sort of thing. Nevertheless, the impression the public had was that it was at least as much my band as his if not more.

“So I can see why he felt pissed off, but you see then it took an extreme form in him, where he felt that to establish his position he had to make out that everything was his. That it could have been any bunch of musicians, that it was his concept and he told us all what to do. Which wasn’t true either, but eventually was manifested in things like when we went to tour Bryan always had a palatial suite to himself, the other band members all had rooms of their own, the drummer’s was the worst always, and the road crew had to bunch together. He had been forced into an extreme position, and that created equally extreme reactions in the other members of the band. I never said it with much seriousness, but it was said sometimes, ‘We don’t fuckin’ need him, we can do it alone,’ which wasn’t true either.

“When the group broke up I thought I didn’t really want to be in a band again, because of all the ego conflicts. Also, it didn’t really seem such a great way of getting music done, because the experience with Roxy was that as soon as it became successful, which was relatively quickly, we’d stop doing the parts that were interesting for me. I liked these endless nights just fiddling around, but then we had to be too purposeful to do that, because there was another tour coming up, ‘Oh god, we’ve got to do photo session,’ etc. Gradually I thought, ‘Well, this isn’t what I want to do, really, it’s all very flattering and so on’ and it was, to suddenly be getting all the attention. We went from being totally unknown to being very well known in about a month, which was very thrilling but didn’t increase our real freedom at all. We spent less and less time working on music and thinking about what we ought to be doing. And that doesn’t mean that we just started relying on a formula–it meant that the experiments that were embarked upon were done less well and less thoroughly. They would just be started upon and then we’d think, ‘Oh, we haven’t got time.’

“Things got rigidified, and necessarily so, because right up until the time that I left the band we never had equipment that was up to our ideals. What we did was quite electronically complicated, using live tapes and all these treatments and quite unusual instruments, like an oboe is a very hard instrument to amplify. We had a difficult sort of band to deal with anyway, and one of the biggest problems that dogged us all the time I was in the band was that we couldn’t hear what we were doing. Nobody could properly hear everybody else. So it meant that to avoid total disasters we couldn’t improvise, or make decisions quickly. Things all had to be agreed, and on top of that we had a complicated light show and what have you, and that was all synched, and we were choreographed and all that sort of thing.”

In the midst of all this Eno formed a friendship and informal working alliance with Robert Fripp, which would drive the wedge between him and Roxy even deeper while it increased his confidence about working with others. He had been doing some experiments at home with tape delay, the kind of experiments that Roxy no longer permitted; this particular set embodied the system that would someday be known as Frippertronics: “I published the diagram for that in 1967, actually. At first I did it with three tape recorders in a chain, then I ended up using two. In fact, I used that on the first Roxy album: there’s one song that has a saxophone treated through that system. But Fripp was the first person I met who actually could use it properly; every other guitar player or musician I met just overplayed immediately. They’d all build up this dense structure that you couldn’t work with at all.

But Fripp immediately understood the use of it; in fact, almost the first time we ever met was when we made the first collaborative album. We’d met once briefly in the office because we shared the same management company, and I said ‘Why don’t you come round sometime, I’ve been doing some things treating guitars that you might be interested in.’ I had that set up already because I’d been working with it myself. So he came over and within about a minute we started doing this thing. He just plugged into it and we taped “The Heavenly Music Corporation” as it was released on No Pussyfooting. It was really interesting, because we did it without discussing it or anything. When we listened to it afterwards he said, ‘I don’t like it that much,’ and I said, ‘Oh, I think it’s really great.’ I kept listening to it and played it for him again about a month later, and he said, ‘Yeah, it’s really good, isn’t it?’

“Then again Richard Williams came into the picture. He came to visit me in this interim between us hearing it and Fripp hearing it again, and he thought it was great, and wrote a little piece about it, much to Bryan’s chagrin actually. This was one of the first big issues in the Roxy breakup, or my part of that. It was like the ‘You’ve got another woman’ kind of thing. I didn’t ask Richard to write this, in fact I wasn’t expecting it at all. He’d come around to listen to something else. Ferry wasn’t aware that I’d done anything with Fripp, because Robert had only just come round for this one evening, you see. So this article came out and Bryan was just really hurt about that, because it was like I was starting my solo career and made it look even more like I wasn’t just a member of Roxy.

“The funny thing is that I wasn’t really feeling particularly limited in Roxy at that time. This was actually a bit before that crisis happened. I was quite happy, though I’d done a little work with Robert Wyatt on Matching Mole’s second album, and I discovered that I really enjoyed working with other people, which is something I hadn’t known musically that I could do. Because my role in Roxy was so peculiar that I thought, ‘What other band could I possibly be in, who else would want to work with somebody like me?’ But when I actually found that there were other people I could work with, it was quite a thrill.”

Eno walks into the recording studio, sets a reel of tape on the floor, and moves immediately to the synthesizer. Flicks a few switches, starts turning dials, and one odd sound after another fills the room–in fact, he seems to be pulling them around through the air like great worms. The tape delay system is already set up, a thin brown line stretching for about a foot between two giant tape recorders. Watching him at the synthesizers, my companion says: “Don’t let him kid you; he may not play any other instruments but he knows exactly what he’s doing.”

What he’s doing today is laying down ambient drones for an album by trumpet player Jon Hassell. A few minutes later Robert Fripp arrives to provide assistance. A few small pleasantries are exchanged between the two men, but Fripp wastes no time in unpacking his guitar, setting up, and then they begin the long slow process: Fripp will seek out a certain little succession of notes or some odd blare on his fretboard, while Eno tries various settings on the electronic bank in front of him. When they hit upon something they like, they let it flow for a while, Fripp playing the same lines over and over while Eno feels his way among the infinite possibilities of what can be done with them, and the tape delay system runs them back over and over each other building to a vast edifice. We sit on a couch down at the front of the room, right in front of the giant speakers, trying to be inconspicuous and feeling very lucky. Not many people have witnessed Fripp and Eno concerts, which is what this amounts to, Fripp standing up with one foot on a stool and the guitar on his knee while Eno bends over the board, complaining between takes about his back. What comes from the speakers over our heads layers upon itself again and again till it seems almost visible, a sonic mountain wall. Recording sessions are usually incredibly dull, but there’s an atmosphere of intense, almost trancelike concentration in this room. The wordless rapport of the two men becomes palpable, then merges with the running commentary of technology in a trinity of engulfing feedback, reminding me of something Eno said during his lecture at the Kitchen festival the other day: “I’m interested in static music, but on a human level. I’m not interested in sequences, but the idea of using human beings as sequencers, because of all the little errors they put in.”

During one break, he laughs: “Sounds like we’ve got a nice Fripp and Eno album here… I don’t know about Jon Hassell,” and describes their methods to the engineer as “a constructive approach to the kitchen sink.”

“It’s interesting,” says Fripp, “that you can produce everything I’ve ever done on that machine.”

“Yes,” smiles Eno. “I just need one note.”

“I’m redundant. Ta!”

Eno begins to tell him about another recent experiment: “I had a radio program going through, clipping out syllables people were saying and making melodies.”

But Fripp is still fascinated, almost with an awe reserved for something creepy, by the synthesizer. “The most interesting thing about electronics is that I’ve spent so many years trying to extend (the) guitar musically, and you plug one of these things in and all you need is one note for all the same things. It’s terrifying… Now I have to practice restraint,” he adds as an almost nervously obligatory joke.

When Fripp is done, he packs up his guitar, says goodbye to all and leaves. There is little banter; it’s almost as if the atmosphere of deep concentration must not be disturbed. He is barely out the door before Eno is back at the board, revving up his drones: “Well, back to the tranquil world of Brian Eno.”

What’s also interesting is how much you immediately miss Fripp. After hearing the two of them, one feels that Eno’s tranquil world is only 50% of an organic whole which represents not electronic noodling but two people intensely listening and creating off of the way their minds seem to complete on another. A while later, when Eno has finished his drones, we mention this to him and he says: “Yes, Fripp always said he played his best guitar solos with me. I think it’s because we don’t get in each other’s way; he’s the virtuoso and I’m the… intuituoso.”

Earlier, as I’d walked him to the elevator, Fripp had commented: “I just can’t communicate with most musicians. It seems always that either they’ve got the technical chops and nothing else, or they’re terrific at conceptualization and can’t play.”

The whole idea of ambient music is delicate enough (and subject to slipping into self-parodying formula at any moment) that one wonders whether any other two players, or either of these by himself, could do it right. In his liner notes for Music for Airports, Eno dismisses Muzak: “familiar tunes arranged and orchestrated in a lightweight and derivative manner,” and insists that his contributions can be used as background (or foreground) music “without being in any way compromised… An ambience is defined as an atmosphere, or a surrounding influence: a tint. My intention is to produce original pieces ostensibly (but not exclusively) for particular times and situations with a view to building up a small but versatile catalogue of environmental music suited to a wide variety of moods and atmospheres… Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

As many critics have pointed out (and as Eno himself noted in the liner notes to Discreet Music), this is very close to Erik Satie, who wanted to make music that could “mingle with the sound of the knives and forks at dinner.” (Perhaps this is why Pierre Boulez once wrote an essay entitled “Erik Satie: Spineless Dog.”) One thinks also of a lot of the woodsier ECM chamber jazz recordings, and as with them even diehard fans may find that there is only so much they can take. Eno laments that “All the positive feedback I’ve gotten on the ambient stuff seems to be from the public; none of my friends like it much.”

Depending on your point of view, Discreet Music, Eno’s most passive piece, is either the definitive unobtrusively lustrous statement on ambient musics or a wispy, treacly bore that defies you to actually pay attention to it. Perhaps the Garden without the sombre reptile that is Fripp, it is also Eno’s very favorite of all his recorded works, perhaps because it was the most painless to make: he just hooked up the synthesizer to a graphic equalizer, echo unit and two tape recorders, turned everything on, and left. “In a way,” he says, “I think my most successful record was Discreet Music. Certainly it was in a sort of economist’s terms of success, because it was done very, very easily, very quickly, very cheaply, with no pain or anguish over anything, and it’s still a good record for me.”

It appears, in fact, that the great and true love of his creative life is the tape recorder, and all of the things it can do. He is neither superstitious nor by-the-book about his little electronic implements, but instead regards them with a certain bemusement. “I’m very good with technology, I always have been, and machines in general. They seem to me not threatening like other people find them but a source of great fun and amusement, like grown up toys really. You can either take the attitude that it has a function and you can learn how to do it, or you can take the attitude that it’s just a black box that you can manipulate any way you want. And that’s always been the attitude I’ve taken, which is why I had a lot of trouble with engineers, because their whole background is learning it from a functional point of view, and then learning how to perform that function. So I made a rule very early on, which I’ve kept to, which was that I would never write down any setting that I got on the synthesizer, no matter how fabulous a sound I got. And the reason for that is that I know myself well enough that if I had a stock of fabulous sounds I would just always use them. I wouldn’t bother to find new ones. So it was a way of trying to keep the instrument fresh. Also I let it decay, it keeps breaking down and changes all the time. There are a lot of things I’ve done before that I couldn’t even do again if I wanted to.”

His compositional method is entirely dependent upon tape recorders, as he neither reads nor writes music, and has occasionally complained about getting an idea for something when he’s out somewhere and being unable to write it down; except that, he has also noted, some of his finest pieces (say, “St. Elmo’s Fire”) are impossible to notate. He “writes” by picking little things out on various instruments, running them through electronics, bringing in other musicians who more often than not have nothing in common with each other, then subjecting the basic tracks to as many overdubs as they’ll need to satisfy them. If everything runs smoothly, he can emerge with something like 1975′s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), the absolute incontestable Eno masterpiece to date. At least a decade ahead of its time, that record’s rich textures, rhythms dancing against each other, and exotic synthesizer treatments of standard rock instrumentation revealed that Eno had already mastered his ultimate instrument: the recording studio. As the overdubs pile up in Byzantine splendor, it’s easy to forget that he made this awesome tapestry with a lineup of guitar, bass, drums and percussion. Guests from Roxy Music, Portsmouth Sinfonia and other sources provided seasoning, and perhaps more than his ambient efforts, Tiger Mountain demonstrated what riches may be mined from the simplest musical materials.

The following year’s Another Green World was the first application of his ambient experiments to actual songs. Where Tiger Mountain had the density and lushness of a thousand-hued tropical forest, Another Green World investigated various possibilities for small ensembles; it was chamber music reconciling the pastoral dells of Eno’s geographic origins with the technological Alphaville that’s his workshop.

Often, his methods make him one of the highest-price talents around, with huge studio tabs: when he went in to cut Before and After Science, he got spooked by favorable press response to Another Green World, and kept endlessly recording, revising, editing, stripping tracks and overdubbing on them again and again. He spent two years writing and recording endless new ones until he’d cut over 120 individual tracks, out of which he finally released ten. And with some anguish: he’d ultimately realized that this project was not going to just resolve itself, that he’d have to stop and release it at some arbitrary point or he’d just go on laboring over it forever.

When I said “resolve itself,” I meant just that: Eno likes to believe that his music has a life of its own, and on the evidence it probably does. He likes to bring the music to a point where he can sort of step aside and let it develop of its own accord, and he has all sorts of devices for making this happen. Some are mechanical, like the Frippertronics tape-delay system, and others are more tactical and organizational, like the piece featuring David van Tieghem where the players could barely hear each other, or the set of cards called Oblique Strategies which he developed with his friend painter Peter Schmidt. The latter are a collection of more-or-less abstract directives from which one may be selected at random when one wants to change the direction in which a given piece is moving; the best-known is “Honor thy error as a hidden intention.”

The main thing is that the result should be, in some sense, a happy accident. “There’s two things happen, I think,” he says by way of explaining his methods. “First of all, you can very laboriously set up a set of conditions, because you hope that at a certain point there’ll be a–snap!–like that, which suddenly the thing will have a direction. But of course often you very laboriously will set up these conditions, and they don’t generate anything. So you set it up deliberately so that it gets to the point where a synergy happens among the elements that you don’t understand; it’s not true that you can make something that you’re finally in control of, rather the opposite thing: you can make something that extends your notion of control.”

He recognizes that leaving at least part of the creative input up to chance processes and machines is asking for a certain otherness in your music, as if an outside entity were codefining it with you, and that one of the hazards of working this way is the loss of some of the more intensely passionate edges. “On the one hand the music sounds to me very emotional,” he says, “but the emotions are confused, they’re not straightforward: things that are very uptempo and frenzied there’s nearly always a melancholy edge somehow. What people call unemotional just doesn’t have a single overriding emotion to it. Certainly the things that I like best are the ones that are the most sort of ambiguous on the emotional level.

“Also, one or two of the pieces I’ve made have been attempts to trigger that sort of unnervous stillness where you don’t feel that for the world to be interesting you have to be manipulating it all the time. The manipulative thing I think is the American ideal: that here’s nature, and you somehow subdue and control it and turn it to your own ends. I get steadily more interested in the idea that here’s nature, the fabric of things or the ongoing current or whatever, and what you can do is just ride on that system, and the amount of interference you need to make can sometimes be very small.”

Of course, this is the sort of thing that could lead someone like New Wave guitarist Lydia Lunch to say: “Eno’s records are an expression of mediocrity, because all it is is just something that flows and weaves, flows and weaves… it’s kind of nauseating. It’s like drinking a glass of water. It means nothing, but it’s very smooth going down.”

Eno himself not only recognizes such criticism but carries it further: “The corollary point is that if you’re not in the manipulative mode anymore you’re not quite sure actually how to measure your own contribution. If you’re not constructing things and pushing things in a certain direction and working towards goals, what is your function? In fact, one of the reasons cybernetics keep coming up is that they do talk about ways of working that are different than that. They talk about systems that are self-governing, so which may not need intervention. They look after themselves, and they go somewhere which you may not have predicted precisely, which is generally in the right direction. But the assessment of these things is, of course, very difficult.”

It may be that Eno has created all his systems as a way of protecting himself against a larger one. If it seems like he’s all over the map (he also dabbles in video and writes occasional prose pieces for English journals), he wouldn’t have it any other way, and it’s not just a matter of being unusually creative, but of knowing what identification in the rock marketplace can do to anybody’s creative drives. “The best thing for me would be to release each album under a different name,” he said in one interview, and like many (most?) real artists he treasures his privacy. The chameleonlike quality of his whole solo career would be seen as one huge defensive tactic against being backed into corners and turned into a cliché by stardom. “I see myself often maneuvering to maintain mobility,” he says. “And I’m certain one of the reasons that my whole kind of selling things is uncoordinated and clumsy is that in fact it acts as a kind of non-constraint to have it be so. The way most bands work is that they release an album, and then the next one, and then the next one, and there’s this kind of linear thing, which tells them what the next album’s got to be like. But what’s happened with me is that since there’s things coming out in all sorts of different ways, like there’s Fripp and Eno and then there’s Discreet Music and then there’s collaborations of various kinds, then there’s the occasional solo album, there isn’t that kind of linearity of development. I still do retain the option of moving around, and people are gonna say, ‘Well, what can you expect, he’s never been consistent.’ And it strikes me as a better position to be in.